Maybe I’m the last to know, but I just found out that the nominal outer diameter of a gauge-numbered machine screw is defined as the gauge number multiplied by .013″, plus .060″. The actual diameter is usually two or three thousandths or so under nominal. I know ’cause we tried it. And as you are all know doubt aware; once you reach a quarter inch, you’re going by fractional inch dimensions instead of gauge. Wood screws go by their own, as yet mysterious to me, system, probably developed by some guy and his partner making screws by hand 250 years ago.

Who cares? Well, we have run into problems with what we refer to as “stacking tolerances” in our production– a threading tap varies slightly (both initially and over time with wear) the anodizing depth varies slightly, and screw dimensions vary slightly even if you stick with one supplier. If these variations all go in the wrong direction at once, you end up with customers calling you saying the screws are so tight in the mount that some of them are breaking, even though you’ve been doing everything exactly the same for years and it’s always worked nicely. We started using +.001″ and +.002″ oversized form taps a few years ago, to make up for the thickness the anodizing adds to the threads, and then some, and the problem went away. Now at least we can measure screws and know exactly how they vary from “nominal” as opposed to making simply comparative measurements.

This new (to me) tidbit of information is just icing on the cake for you engineers out there, in the unlikely event that you were as ignorant of such things as I was a few minutes ago. What I still don’t understand is why we call a number eight screw a number eight screw instead of a .164″ screw. Too many digits? But then you’d not have to remember gauge x .013″ + .060″.

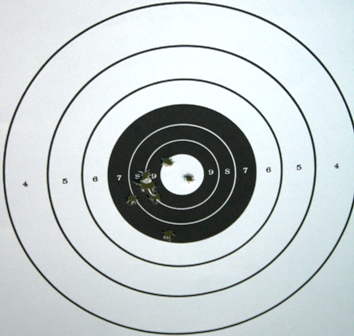

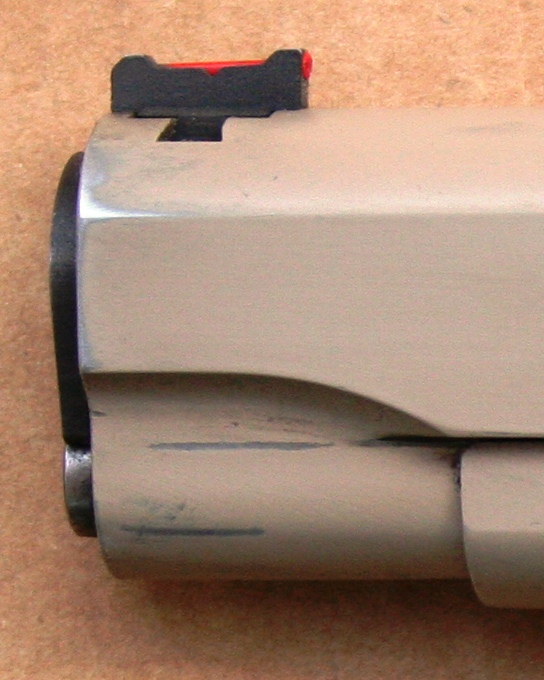

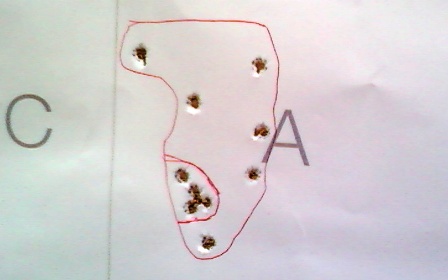

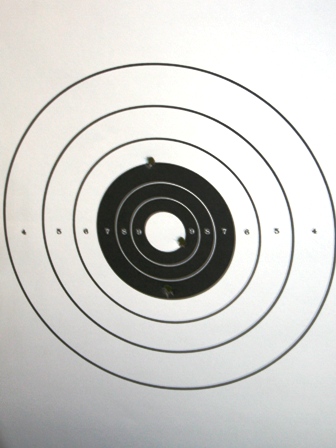

Some of these oddities come down from the past in “organic” ways. Firearm bullet and bore diameters are a good example. Who the hell came up with .223, .308 or .452, as opposed to, say .200, .250, .300 .350, etc? Some of these unlikely numbers, at least in part, come from the days of black powder, wrought iron barrels, soft lead bullets, and the manufacturing tolerances of yore. The realistic tolerances back then were nowhere near what’s possible now, and it resulted in some pretty weird numbers that became standards out of expediency and in response to backward compatibility issues. I use a .454 ball (that number’s still with us) in an 1850s .44 percussion revolver for example, because the oversized ball gets better purchase on the sides of the chamber and on the rifling. We would now refer to a .454 bullet as caliber 45, though you were shooting it from what was called a .44 caliber pistol back in the 1860s, and the modern 45 cal bullets are .451″ and .452″. Modern 44 caliber bullets are .429″. Huh? I definitely need to learn more about this stuff. In another .44 percussion revolver I have I use a .457″ ball– you want a ball that’s bigger than the cylinder, and a cylinder that’s bigger than the barrel groove diameter, so everything gets a sure, tight fit with the soft lead ball.

We still use grains as a unit of measurement, which came from some king somewhere telling us that the official definition of a pound was “seven thousand plump grains of wheat” (what poor saps had to count them, then recount them, and who verified their work?). Shotgunners use the dram, which converts to the tidy number of 27.34375 grains, or the “dram equivalent”, which is a charge of modern smokeless powder that generates about the same energy as that number of drams of black powder.

If we were to start all over and reinvent guns from the beginning today, we’d no doubt end up with simpler units and numbers, but the world doesn’t work that way. Each incremental development is built upon the previous one, and you don’t immediately re-tool everyone in the business, make all the old versions unusable, and change all the established experience and data, just for that little increment of improvement.

Still, I keep saying someone needs to reinvent the computer OS (or the very concept of the computer OS– maybe the very use of the term “OS” is thinking too much inside the box) from the beginning. There is of course no basis– no established school of thought or system of evaluation that would warrant such a claim.

Like this:

Like Loading...