A week or two ago Ry showed up in my office and said he wanted to do an experiment. He and I have had conflicting information on the contamination of primers by oil. The common word on the Internet and word of mouth is that if you get the tiniest amount of oil on the chemically active portion of a primer then it would go dead.

However Ry had seen Lyle demonstrate this was not true by putting CLP in a shell casing with an active primer then detonating it a minute or two later. I had done similar things myself. I wanted to deprime some cases with live primers and to test the “kill the primer with oil” hypothesis I put a thin oil in the mouth of a shell casing and waited, sometimes a day or more, but they would still fire just fine. Bah! As usual the Internet is wrong. Right?

As we talked about the experiment we realized the Internet story wasn’t quite the same thing as our first hand data. Our first hand data wasn’t of putting oil directly on the primer. It was putting oil in the mouth of a shell casing. We believed the thin oil would make it through the flash hole into the active area of the primer.

But that was an assumption. It was not a proven fact.

So what we decided to do was soak the primers for few minutes in a paper cup and then load them in a shell casing. We would do several primers then test them at various time intervals, like an hour, a day, a week, and a month. We expected the primers would still be fine after a month and the myth would be busted.

Here are the solvents we tested:

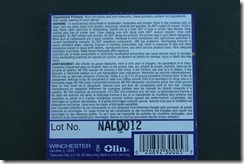

We used Winchester small pistol primers:

Here are the primers being soaked prior to inserting on the empty shell casings:

An interesting thing occurred. The primers soaked in Break Free CLP turned the CLP slightly red after a few minutes:

And the primers in the water turned the water slightly yellow:

We also created two control sets. One set had dry primers in a dry shell casing and the other set had dry primers with solvent put in the shell casing.

After we had all the shell casing loaded Ry added more of the solvent to the test shell casings so evaporation would not be a factor in the long term testing.

We then tested both control sets and the test set.

We hand loaded the empty shell casings into a handgun and put the muzzle tight against an air pillow used for padding in Amazon shipments. We then fired the gun. If it failed to fire we would cock the hammer and try a second time. If it failed both times we called it a dead primer. There were no primers which failed on the first attempt and succeeded on the second. If it popped the air pillow it was a “vigorous” detonation. If it failed to puncture the air pillow it was a “mild” detonation:

The dry normally inserted primers would punch a hole through both sides of the air pillow even though there was a significant air gap between the two sides:

We tested two primers for each solvent. The results with solvent only in the shell casing mouth were as follows:

| Solvent |

Detonation Result |

| Water |

2 vigorous |

| Break Free CLP |

2 vigorous |

| WD 40 |

2 mild |

| 3-IN-ONE |

1 vigorous, 1 mild |

| Tetra Gun Lubricant |

2 vigorous |

This confirmed the tests Lyle and I had done years ago. The primers were still active after putting oil in the case mouth.

Here are the results of the primers soaked in the paper cups with solvent:

| Solvent |

Detonation Result |

| Water |

2 dead |

| Break Free CLP |

1 mild, 1 dead |

| WD 40 |

1 mild, 1 very mild |

| 3-IN-ONE |

2 mild |

| Tetra Gun Lubricant |

2 mild |

We will have updates later after the remaining primers have soaked for longer periods of time but it is clear that the flash hole is a significant barrier to the entry of solvents into the primer compound and the common wisdom of oil damaging primers is true.

Update from Ry after one day:

| Solvent |

Detonation Result |

| Water |

2 dead |

| Break Free CLP |

1 mild, 1 dead |

| WD 40 |

1 very mild, 1 dead |

| 3-IN-ONE |

1 mild, 1 dead |

| Tetra Gun Lubricant |

2 dead |

Like this:

Like Loading...